★★★½ (3½ out of 4)

I kept smiling, even laughing out loud watching “The Love That Remains.” A bizarre reaction I guess for a movie about the end of a marriage. But it’s the high-spirits that Icelandic writer-director Hlynur Pálmason infuses into his family-centered dramedy that stay with you. Pálmason doesn’t neglect bruised feelings—a strain of sadness runs through the film but never dominates it. This is a family, and I’m including their scene-stealing dog Panda, that knows how to find strength and frisky humor in what remains behind.

That playful touch marks a difference from the bleak aura of Pálmason’s first three films: "Winter Brothers,” “A White, White Day” and the Oscar short-listed “Godland.” Pálmason’s background in visual art can be felt in his preference for show over tell. Characters don’t pour out their feelings in words. You intuit those feelings by paying close attention to nuance in behavior and the images he puts before us.

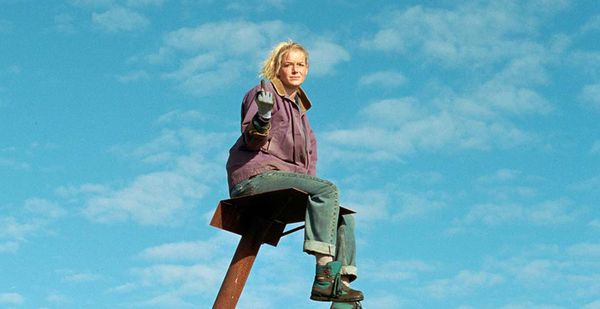

And what images! The film begins with a visual metaphor of destruction as a crane lifts the roof off a building, exposing what’s inside to the elements. The property was once a studio used by Anna (the sublime Saga Garðarsdóttir), a struggling artist whose world is coming apart in more ways than one. She’s also separated from her husband Magnus (nicknamed Maggi and played by Sverrir Guðnason), who’s often away working on a fishing trawler.

The director’s dips into surrealism can feel bluntly miscalculated, but the way he sets his love for humanity against the hard truths of living in a broken marriage creates a film that takes a piece out of you, if you let it. Let it.

If Maggi’s absences are one reason for the breakup, you won’t hear that here. When Maggi is home, he and Anna have sex but keep it from the kids to avoid giving the wrong impression. The kids—a teen girl and twin sons—are played beautifully by the director’s own children, Ída Mekkín Hlynsdóttir, Þorgils Hlynsson and Grímur Hlynsson. And they don’t miss much about what’s going on with their parents.

Over one year, we see them on family outings, enjoying the changing seasons (Pálmason is also the film’s gifted cinematographer) and each other’s company. Their mischief is vibrant, sometimes even vulgar, but you can feel the raw emotions roiling inside.

It’s impossible not to have your heart stolen by Panda, the Icelandic sheepdog (yes, he’s also part of the Pálmason family) whose antics helped win him the coveted Palm Dog at the prestigious Cannes Film Festival where the film debuted. Messi, the border collie from “Anatomy of a Fall,” is a former winner, so Panda is barking in good company.

What we are watching in this remarkable film is a family adjusting to a new way of living and to the hurt and healing that goes along it. Pálmason clearly identifies with Anna’s struggle as an impressionistic artist, using the rust of the metal materials she works with to define a creative world that may not be sustainable. And his sympathies for Maggi’s pain come through strongly in Guðnason’s deeply felt performance as a husband and father whose roles are now blurred by an intimacy-killing distance.

From the gentle hush of Harry Hunt’s piano score to the roar of nature itself, “The Love That Remains” is a mesmerizer that gets the details. It’s not that Pálmason has no faults. His dips into surrealism, especially near the end, can feel bluntly miscalculated, as does his refusal to let his characters actually speak their secret hearts. But the way he sets his love for humanity against the hard truths of living creates a film that takes a piece out of you if you let it. Let it.