★★½ (2½ out of 4)

Glen Powell plays a premeditated, cold-blooded murderer in “How to Make a Killing,” now in theaters where you’re going to love this American psycho anyway, because for starters he’s played with charmingly sexy flair by Glen Powell, and secondly because everyone he kills is a one percenter. As Ariana Grande taught us in song, “No one mourns the wicked.”

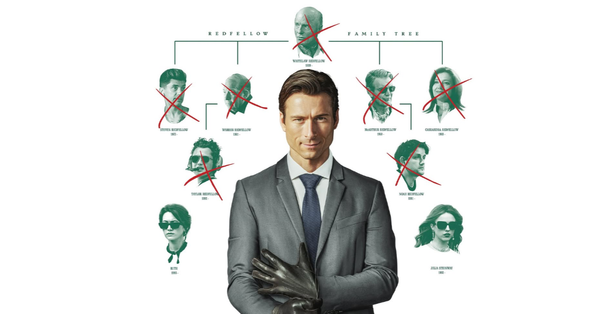

Powell has a great character name in Becket Redfellow. His family is billionaire rich, but he isn’t, having been disowned at birth by granddad Whitelaw Redfellow (Ed Harris, trying way too hard) for being the illegitimate spawn of teen Redfellow heiress Mary (Nell Williams) and a random musician (Damien Wantenaar). Becket is cast out when Mary refuses a family-sanctioned abortion, preferring to raise Becket alone in the downscale suburbs of—oh god no!—New Jersey. Her dying wish to her son, shunted off to foster care, is: “Promise me you won’t quit until you have the right kind of life.” Seed planted.

As for the family fortune of $28 billion, Becket —now uncomfortably working basement retail in menswear—tells his childhood friend, Julia Steinway (the flirty and forever fabulous Margaret Qualley), that he will inherit the entire bundle one day. “Let me know when you kill them all,” Julia quips. Second seed planted. The trouble is that there’s a whopping seven other Redfellow cousins ahead of Becket on the inheritance list.

Any movie scholar worth the name (and what are you doing on this blog if you’re not?) will know this plot is right out of “Kind Hearts and Coronets,” the 1949 British black comedy that’s considered a classic of the Ealing Studio era. Dennis Price played the Powell role, but it was Alec Guinness who took another step on the ladder to screen immortality by embodying all the victims, including the women, adding drag to his list of expert talents.

Sadly, Powell limits himself to the avenger role, leaving seven separate actors to go for the comedy gusto as the victims. I don’t know about you, but I feel cheated. No knock on writer-director John Patton Ford, who impressed with his 2022 debut film, “Emily the Criminal,” starring the inimitable Aubrey Plaza, but holding back Powell is an opportunity missed. Some really do like it hot and Powell did seriously well with disguises in Richard Linklater’s “Hit Man,” still his best movie performance to date.

By the end, the lockstep quality of this murder comedy commits the worst crime of all by killing our interest.

So let the record show that “How to Make a Killing” is miles off the top-drawer league of “Kind Hearts and Coronets,” though Powell slathers his undeniable charisma all over it. It also can’t hold a candle to last year’s “No Other Choice,” Park Chan-wook’s latest masterpiece about living well maybe not being the best revenge.

No sense in getting all morally judgy about the victims since the filmmakers don’t. “How to Make a Killing” opens with Becket on death row confessing his sins to a priest to show, I guess, that crime doesn’t pay, even though we know all too well from daily headlines that it pays extremely well.

Patton Ford paces the film nicely, at first, jumping from homicide to homicide with aplomb. The tradeoff is that the momentum sacrifices most chances to dig deeper or show a demonstrable working conscience. The actors get an A for effort, but it’s all downhill from there. Obnoxious financé cousin Taylor (Riff Law) goes first by drowning, since Becket tied an anchor to his ankles, while a darkroom explosion ends shutterbug Noah (Zach Woods), giving Becket a chance to hit on Noah’s honey Ruth (a terrific Jessica Henwick), who may know more than she’s letting on.

Topher Grace gets his licks in as an unholy roller, religious hypocrisy made flesh. And the great Bill Camp is surprisingly relatable as Warren, the elder statesman who seems to be keeping the books at the family brokerage firm without cooking them. The corruption in the Redfellow clan traces back to big daddy Whitelaw, but by then this murder comedy has committed the worst crime of all by killing our interest. Despite Powell’s best efforts, coulda-woulda-shoulda is never worth the price of admission.